Analysis

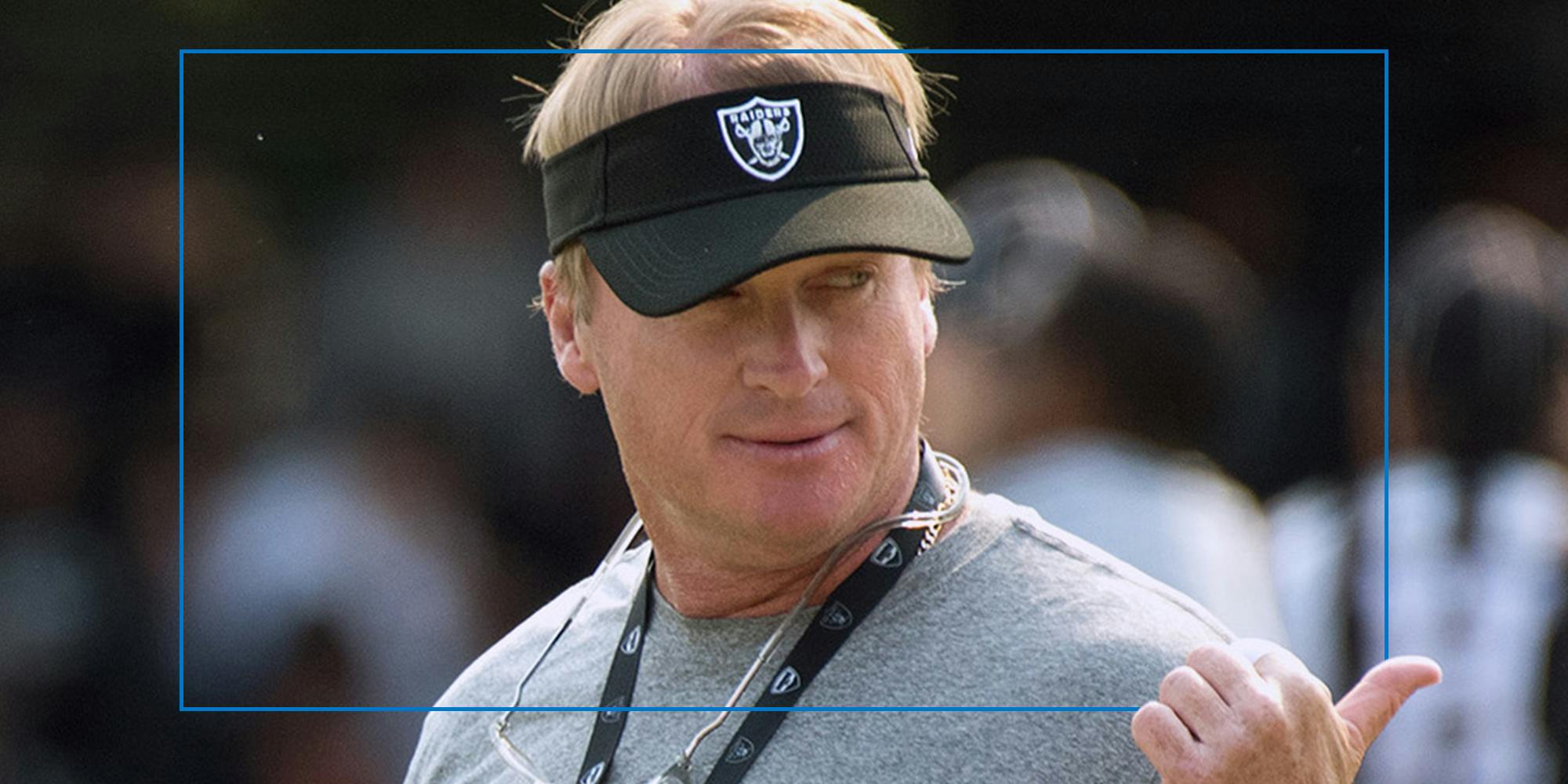

Jon Gruden resigned as head coach of the Las Vegas Raiders on Oct. 14 after several emails containing racist, sexist, homophobic, and other problematic messaging were released. According to Pro Football Talk, the old emails only came to light because of an investigation into the Washington Football Team. Yet at first Gruden received the proverbial slap on the hand.

When the racist emails he sent to Bruce Allen, the team's former president, came out on Oct. 10, which included racist remarks on the physical appearance of NFLPA union head DeMaurice Smith, the public majority ostracized Gruden online. The NFL, as an institution, was swiftly escorted away from his radioactivity, leaving him to hold the bag of ignoble -isms. And the consumer allowed it, business as usual. But why? How was this made possible?

"Dumboriss [sic] Smith has lips the size of michellin [sic] tires," Gruden wrote years ago, according to the Wall Street Journal's Andrew Beaton, though he more recently claimed he was trying to call Smith a liar. "I don't have a racial bone in my body, and I've proven that for 58 years," Gruden told Beaton. Many former players-turned-analysts were hurt by the comments from an email trove dating from 2011 through 2018.

While he had possibly lost trust with his Black players, he was publicly defended; many even believed that Gruden should be allowed to continue as head coach. He would, in fact, coach the following Sunday, a 20-9 loss to the rebuilding Chicago Bears. Mike Tirico and Tony Dungy, Black men, long associated with the NFL and currently leads on NBC's programming, wore capes for Gruden.

"Part of that is because there was a personal investment in Jon Gruden's success, many levels," said Phillip Lamar Cunningham, associate professor in media studies at Wake Forest. "He's always been presented as a bit of a golden boy."

Concerning Tirico and the endlessly forgiving Dungy, Cunningham sees their response as part and parcel with their public media personas.

"Dungy as always being a conciliatory peacemaker, a guy who could sort of see both sides, whereas Mike Tirico, in many regards, one always distanced himself from Blackness," he said, recalling the latter's heavy lean into his Italian heritage.

However, once the sexist and homophobic emails—specifically calling commissioner Roger Goddell a "f*ggot" and using the word "qu**rs" in the pejorative—hit publicly after the racist messages, a collective public shaming arrived alongside Gruden's resignation. Why didn't Gruden's racism alone lead to more similar consequences? And why was he alone singled out? The answers feel as evident as the question. Yes, racism; always racism. But answers come into the light, one after another, simultaneous but separate discovery.

Anchored in racism

While the release of the entire email trove is welcome and necessary, it is critical to note that it is part of a broader investigation of the oft-beleaguered Washington franchise. Unbelievably, per the Associated Press, the NFL says that "no other current team or league personnel to have sent emails containing racist, homophobic or misogynistic language similar to messages written by Jon Gruden" within the "650,000 emails the independent investigators collected during an investigation of sexual harassment and other workplace conditions at the Washington Football Team."

It seems more likely that Gruden became the sacrificial lamb for numerous parties, mainly the league's owners.

However, let's suppose the NFL found no additional problematic language; the idea that Gruden could be so comfortable sending these emails and Allen receiving them—over eight years to a club president no less and without thought to repercussion—is informative. This is perhaps because the NFL isn't a proactive stalwart regarding race; it could even be said that the league has anchored itself in institutional racism.

For example, for 12 years, from 1934 to 1946, NFL team owners mutually agreed to a de facto ban of Black players. In 1974, former bone-crushing defensive back Dick "Night Train" Lane detailed what was already a longstanding issue during his Hall of Fame induction speech: "I can only hope that while the players are striking for improvement that the Black players will take this opportunity to band together and deal with the problems of no Black coaches, no general managers and no quarterbacks in the NFL, or I should say a few. It is not fair or pardonable for Blacks to be treated like stepchildren in pro football. It was wrong in my day, and it is wrong today."

The subsequent decades-in-the-making "Rooney Rule" requires franchises to interview ethnic-minority candidates for head coaching and senior football operation positions. However, it has been flouted consistently and with limited penalties since its inception in 2003. Though the NFL is primarily a league of Black men, they apparently are rarely qualified to coach. The justifications for this reality and Gruden's comfort in racism, and people's forgiveness of said racism, lie in how the league and its members frame and consider Black people.

Racism on the brain

This summer, an illuminating discovery stemming from a separate NFL inquiry, turned a few heads. In June, the league announced it would end the practice of "race norming" when defining eligibility for compensation in its $1 billion concussion settlement. Two former players—Kevin Henry and Najeh Davenport—are currently suing the NFL for the usage. According to a recent Washington Post report, "the league and its lawyers have continued to defend the practice in public statements and court filings" since the June announcement.

They publicly pledged to stop race-norming this week. The league's lawyers keep defending it.

Rooted in ideas dating back to slavery, "race norming" is a practice based on the assumption that Black people fluctuate from a baseline of assumed white norms. The NFL's settlement was based upon two standards—one for Black players and one for white players—in accessing cognitive impairment and awarding values. By using the league's "Baseline Assessment Program," clinicians also followed the NFL's concussion settlement program manual, which recommended "full demographic correction," using what amounted to tiered, race-specific cognitive scores. The Post story describes that a "confidential guidebook directed doctors to use several tests and score-curving systems that require race-norming." Per an NBC News report, "retired Black players were assumed to have lower baseline levels of cognitive function than retired white players. Black claimants, then, had to demonstrate more impairment to receive the same financial awards as their white counterparts."

In essence, the NFL—its administrators and the 32 franchisees collectively—have codified (and defended) a racist, mutually agreed-upon notion that cognitive impairment could not be as likely among Black players because Black people, on the whole, already suffer from fundamentally substandard mental faculty compared to white people. There's an idea that sports endure in a vacuum where race does not exist; however, these rules that the NFL disputes are still applicable rest upon hundreds of years of racist thought, alongside the gross disenfranchisement of Black people and inhuman valuations of Black bodies and minds.

These ideas inform the basis from which the NFL and its members have proceeded in business, including the disposal of its Black athletes and the non-engagement of Black brainpower. I think it's the reason Gruden was not fired upon the discovery of racist emails, as this societal ill isn't a dealbreaker in the NFL. I think it is the reason that NBC News wrote, still confirming "Night Train" Lane's complaint decades later, that "nearly 40% of head coaches hired from the 2009-10 season through the 2018-19 season were offensive coordinators, and 91% of the coaches hired as offensive coordinators in that same time frame were white," per Arizona State University's Global Sport Education and Research Lab.

The banality of racism, woven into the fabric of America, has become normalized, as has the assurance of the NFL's sanctity.

Inconvenient truths

Football exists as an American utility; the NFL and its corporate partners understand this better than anyone. Because we see the NFL essentially as electricity, anti-Blackness isn't a direct output, much less a feature. The fact that there has been precisely one Black team president in NFL history doesn't register, just as board members of a regional water company aren't on most radars. They know you need water; the NFL knows you need football.

How does one challenge a pleasure utility? Who has the authority? It begets more questions than answers.

"I think with all things NFL, I'm always left asking myself, 'Who makes the NFL pay consequences?'" said Cunningham, on consideration of the system vs. single actors, like Gruden. "The NFL self-policing mechanisms are poor across the board, and we could see that play out with the reactions to the Ray Rice issue. And when they did start throwing down a law about what a rule violation looks like, it was inconsistent and often poorly applied."

"The question is 'What do we, the consumer, ask of the league?' Consumers have to start asking themselves questions about what the league does and how we respond to it. And if we're not going to get mad about it, and we're not going to truly penalize the league, why would you change? And I don't know that we, the consumer, ask enough of the league itself because we don't like the disruption. When September comes around, we want football to be there."

The post How Jon Gruden became a sacrificial lamb for the NFL—a league anchored in racism appeared first on The Daily Dot.

0 Commentaires